Art Adventure • 7.30.2023 • Elusive Blue

Gleba mentions a blue pigment deposit near abandoned mineral springs in Hopkinton, Mass. One Joel Norcross “discovered” the springs in 1815 while repairing his sawmill after a tornado and electrical storm (though surely they were known to the Native Americans who had been in the area for millennia). An analysis of the water from the three springs confirmed the presence of sulfur, magnesium (or manganese) and iron. Norcross built a luxury hotel and made the springs accessible to visitors. The resort attracted presidents, senators, millionaires and high society for four decades until the hotel burned to the ground in the mid 1800s, according to an article about the Old Connecticut Path.

Some sources, including the Boston Globe, say that today nothing remains of the springs or the hotel. But enter a Hopkinton High School senior, James Regan, who made researching the springs his Eagle Scout project in 2009.

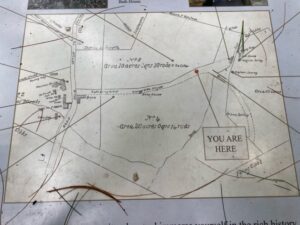

Several others sources mentioned vague (and different) access routes. An 1831 map preserved by Regan shows the location of the hotel and the springs 0.3 miles north of Bear Hill Cemetery. The half-acre cemetery is Hopkinton’s oldest and burials date back at least until the late seventeenth century. Google Maps knows where the cemetery is located and a third of a mile is about 800 steps, so maybe this would be enough information. On the other hand, I also had information that the springs could be accessed off Lyford Road, though I had no directions from there.

Abby Heim and I met at Caffe Nero in Burlington and headed out the Mass Pike early (for me—it was about 10:30 a.m.) on what promised to be an extremely hot day. The early start was to try to avoid the worst of the heat.

We found Lyford Road, a short street ending in a cul-de-sac, parked the car, put on bug stuff, collected our prospecting gear, and donned boots (me, not Abby, whose lack of fear of snakes I have mentioned before), and set off into the woods. There were two stone walls marking a path, so we were optimistic until we ended up in somebody’s backyard on very marshy land. But a marsh is not a spring, so we turned around. (I think we had stumbled upon a section of the Old Town Road, which had originated at a cart path in the early eighteenth century.)

We went back to the car to try the other side of the road (seems to be a pattern here), where we espied a nearly hidden, nearly illegible wooden sign, “Public Walkway.” A walkway to where, though?

But it was our best (and only) clue about what to do next and we followed the trail about a quarter of mile into the woods where we came upon three mostly-still-intact interpretive signs that were placed there as part of Regan’s extremely well-researched project.

There were no remains of the hotel visible, but the three springs were very clearly marked on the map, and we had no trouble finding them, still burbling away. The stone structures built by the resort around the springs were also largely intact.

There were no remains of the hotel visible, but the three springs were very clearly marked on the map, and we had no trouble finding them, still burbling away. The stone structures built by the resort around the springs were also largely intact.

There were indeed beautiful blue stains on the rocks around the magnesium/manganese spring. We collected a small one to take with us.

And this is where things become confusing. The stain was just that—a very thin layer of blue that would be a difficult to get off the rock. The chances of getting enough of it, even if we scraped every rock, to make into pigment for a painting were zero to slim. Let alone getting enough for the spring to be mentioned as a source of commercial pigment.

The color was a glorious light aqua. But magnesium leached from water stains white, and manganese stains orangey-brown. Winsor & Newton has a beautiful manganese blue oil paint that is nearly the right color; however, it is an inorganic synthetic substance discovered accidentally in 1907. According to Winsor & Newton, manganese blue “was produced by heating sodium sulphate, potassium permanganate and barium nitrate at 750-800 degrees Celsius to create barium manganate,” until barium manganate fell out of use in the 1970s, presumably because of its toxicity. W&N now offers a manganese blue hue, but offers no information about its source, except that it is a synthetic.

The color was a glorious light aqua. But magnesium leached from water stains white, and manganese stains orangey-brown. Winsor & Newton has a beautiful manganese blue oil paint that is nearly the right color; however, it is an inorganic synthetic substance discovered accidentally in 1907. According to Winsor & Newton, manganese blue “was produced by heating sodium sulphate, potassium permanganate and barium nitrate at 750-800 degrees Celsius to create barium manganate,” until barium manganate fell out of use in the 1970s, presumably because of its toxicity. W&N now offers a manganese blue hue, but offers no information about its source, except that it is a synthetic.

Thanks to Abby, we have beautiful photos of the springs and rocks and I have asked a botanist to look at them and perhaps offer an opinion about what the blue patches are. I suspect they are lichen.

So to date, I have yellow and red ochre to make into pigment, but the third primary color, blue, as always, remains elusive. Remember lapis lazuli, once worth its weight in gold because it was so rare?

Blue is my favorite color, and my search for a blue pigment continues, but whether it will lead to the forest, the garden, the beach, or the laboratory remains a mystery. Glebe does mention several locations of blue clay on Cape Cod, so maybe I’ll have a look when I go down to Provincetown next week to look at galleries where my paintings might work. Stay tuned.